Eagle 20 and Myclobutanil in the Context of Cannabis Cultivation and Consumption

5/14/2015

14 Comments

Overview

On March 23rd, several Denver-based marijuana grow operations were ordered to quarantine plants after it was determined they were treated with

Eagle 20, a fungicidal pesticide (1). Myclobutanil-based fungicides, including

Eagle 20, are applied to a wide range of edible agricultural products (grapes, apples, spinach, etc). When applied correctly, myclobutanil is known to have low toxicity to humans. Myclobutanil-based fungicides, including

Eagle 20EW, are not currently approved for use in the United States on tobacco, the only (other than marijuana) smokable agricultural commodity. The toxicity and health effects of myclobutanil in the context of combustion/inhalation (versus ingestion) have not been assessed.

The following analysis summarizes some of the known chemical and physical properties of myclobutanil, and highlights the potential health implications of using this chemical on marijuana.

Mode of Action

Myclobutanil is the active ingredient in several brands of pesticides, including

Eagle 20EW. Myclobutanil works by blocking a key enzyme involved in fungal cell membrane synthesis, leading to abnormal cell growth and eventual death of the fungal pathogen (2) Myclobutanil is a systemic fungicide, meaning it is absorbed at the site of application (ex. leaf) and distributed throughout the rest of the plant, thereby providing more comprehensive protection from fungal infection (2). As a systemic chemical, myclobutanil cannot be removed by washing treated crops, although residue will decrease in plant tissues over time. The final remaining residue levels vary considerably and are highly dependent on the rate of application, the time of last application before harvest, and how well the specific plant clears the chemical from its system.

Myclobutanil Tolerance Levels

The Environmental Protection Agency is responsible for regulating the pesticides used by growers to protect crops and for setting limits on the amount of pesticides that may remain in or on foods marketed in the USA. These limits on pesticides left on foods are called "tolerances" in the U.S (3).

The EPA establishes tolerances or each pesticide based on the potential risks to human health posed by that pesticide, using actual or estimated residue data, as well non-human toxicity studies, to reflect real-world exposure as closely as possible (3).

Tolerance levels for myclobutanil were established for exposure via inhalation, absorption through the skin during pesticide application to crops, and ingestion of agricultural commodities treated with myclobutanil. Myclobutanil absorbed by the most common route, dietary exposure, is metabolized by gut enzymes and the liver prior to entering the bloodstream (4,5). Myclobutanil absorbed via inhalation enters the bloodstream directly via the lungs.

I. The human health effects from the combustion and inhalation of myclobutanil have not been evaluated

Tolerance levels and toxicity studies for myclobutanil on edible products should not be used for evaluating the safety of myclobutanil on marijuana. Passage of pesticides into the bloodstream varies considerably between inhalation and ingestion routes of exposure, and the application of high temperature is known to alter the chemical composition of myclobutanil. Unfortunately, very little information is available to evaluate myclobutanil in the context of tobacco use, as

Eagle 20 and myclobutanil-based fungicides are not approved for use on tobacco plants in the United States (6,7). Myclobutanil is approved for use on tobacco cultivated in China, however, and a 2012 study has demonstrated that 10% or more of the active pesticide remains on tobacco leaves up to 21 days after treatment, with residue present from 0.85 parts per million (ppm) up to 3.27 ppm (8). Using tobacco as a model for pesticide retention, it is probable a considerable amount of myclobutanil may remain present in cannabis weeks after fungicide application.

II. Inhalation of pyrolized myclobutanil residue could expose cannabis users to hydrogen cyanide

As noted on the

Eagle 20 material safety data sheet(3), myclobutanil is stable at room temperature, but releases highly toxic gas if heated past its boiling point of 205°C (401°F) (3, 9). Disposable butane lighters, commonly used to ignite marijuana during consumption, produce temperatures in excess of 450°C.

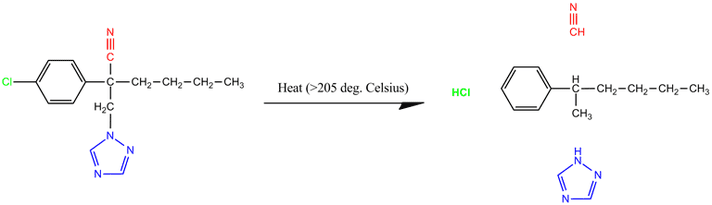

Figure 1. Chemical structure of myclobutanil and decomposition products. Cyanide moiety indicated in red, chlorine indicated in green, and triazole moiety indicated in blue.

As shown in Figure 1 above, myclobutanil decomposes, its triazole (Figure 1, blue), cyanide (Figure 1, red) and chlorine (Figure 1, green) moieties are released and form toxic gases, including hydrogen cyanide (HCN) and hydrochloric gas (HCl). Of the three primary decomposition products formed, HCN holds the greatest concern. Chronic exposure to dilute hydrogen cyanide (ex. 0.008 parts per million) is not immediately deadly (10), but is known to cause serious neurological, respiratory, cardiovascular, and thyroid problems (11, 12, 13). Cannabis retaining even marginal amounts of myclobutanil (ex. 0.03 ppm) could potentially expose consumers to non-lethal, but clinically relevant levels of HCN.

III. Myclobutanil is co-extracted with cannabinoids during concentrate production

Studies of two other conazole fungicides, tebuconazole and propiconazole, have demonstrated that these chemicals are co-extracted during production of essential oils (14). Moreover, the process of extraction, treatment, and concentration can cause tebuconazole and propiconazole pesticide residue to accumulate at levels 250 times higher than the starting material (14). Myclobutanil is highly soluble in many of the solvents used in cannabinoid extraction (ex. ethanol, butane, and carbon dioxide)(15,16), and unquestionably co-extracts with cannabinoids during concentrate production. The process of removing residual solvent and increasing cannabinoid concentration very likely increases levels of myclobutanil, and other chemically-similar pesticides.

Conclusion

The Colorado Department of Agriculture has identified and published a list of "minimum risk pesticides" that pose little or no risk to human health (18) and are allowable for use on marijuana during cultivation.

Eagle 20 (myclobutanil) is not on this list, but the absence of regulatory oversight has contributed to its widespread use in marijuana cultivation in Colorado.

Federal guidance is unlikely, given the legal status of marijuana. It falls on Colorado to build on the guidelines issued by the CDA to implement more stringent regulation, including pesticide residue testing, to prevent tainted product from reaching the open marketplace and consumers.

References

1. Cotton, Anthony. "Pesticide Misuse Puts Pot Plants at Six Denver Grow Facilities on Hold."

Denver Post, 24 Mar. 2015. Web. 5 May 2015.

2. "Specimen Label:

Eagle 20EW - Specialty Fungicide."

Crop Data Management Systems. Crop Data Management Systems, Inc, 21 Sept. 2011. Web. 5 May 2015. <

http://www.cdms.net/LDat/ld6DG004.pdf>.

3. "Material Safety Data Sheet:

Eagle 20EW - Specialty Fungicide."

Crop Data Management Systems. Crop Data Management Systems, Inc, 25 May 2012. Web. 5 May 2015. <

http://www.cdms.net>.

4. "Pesticide Tolerances."

Pesticides: Regulating Pesticides. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 4 Feb. 2014. Web. 5 May 2015. <>.

5. "Myclobutanil."

ToxNet: Toxicology Data Network. U.S. National Library Of Medicine, 2 June 2008. Web. 5 May 2015. <>.

6. "Myclobutanil; Pesticide Tolerance. a Rule by the Environmental Protection Agency on 03/26/2008."

Federal Register. National Archives And Records Administration, 3 Mar. 2008. Web. 5 May 2015. <

https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2008/03/26/E8-6205/myclobutanil-pesticide-tolerance>.

7. Daley, Paul, David Lampach, Savino Sguerra, and BOTEC Analysis Corporation. "Testing Cannabis for Contaminants."

Washington State Liquor Control Board. Washington State, 12 Sept. 2013. Web. 5 May 2015. <

http://liq.wa.gov/publications/Marijuana/BOTEC reports/1a-Testing-for-Contaminants-Final-Revised.pdf>.

8. Pfeufer, Emily, and Bob Pearce. "2015 Fungicide Guide for Burley and Dark Tobacco."

College Of Agriculture, Food And Environment. University Of Kentucky, Jan. 2015. Web. 5 May 2015. <>.

9. Wang, X, Y Li, G Xu, H Sun, J Xu, X Zheng, and F Wang. "Dissipation and Residues of Myclobutanil in Tobacco and Soil Under Field Conditions."

Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 88.5 (2012): 759-763. Web. 5 May 2015.

10. Sun, Xiao-Hong, Yuan-Fa Liu, Zhi-Cheng Tan, Ying-Qi Jia, Mei-Han Wang, and You-Ying Di. "Heat Capacity and Thermodynamic Properties of Myclobutanil."

Chinese Journal of Chemistry 23.1 (2005): 23-27. Web. 5 May 2015.

11. "Cyanide Compounds."

Air Toxics. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Jan. 2000. Web. 5 May 2015. <>.

12. El Ghawabi, SH, MA Gaafar, AA El-Saharti, SH Ahmed, KK Malash, and R Fares. "Chronic Cyanide Exposure: a Clinical, Radioisotope, and Laboratory Study."

British Journal of Industrial Medicine 32(1975): 215-219. Web. 5 May 2015.

13. "Toxicological Profile for Cyanide."

Agency For Toxic Substances & Disease Registry. U.S. Department Of Health And Human Services, July 2006. Web. 5 May 2015. <

http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp8.pdf>.

14. Blanc, P, M Hogan, K Mallin, D Hryhorczuk, S Hessl, and B Bernard. "Cyanide Intoxication Among Silver-reclaiming Workers."

The Journal of the American Medical Association 253(1985): 367-371. Web. 5 May 2015.

15. Tascone, O, C Roy, JJ Filippi, and UJ Meierhenrich. "Use, Analysis, and Regulation of Pesticides in Natural Extracts, Essential Oils, Concretes, and Absolutes."

Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 406(2014): 971-980. Web. 5 May 2015.

16. Tomlin, C.D.S. (ed.).

The Pesticide Manual - World Compendium, 11 th ed., British Crop Protection Council, Surrey, England 1997, p. 854

17. Ackerman P et al;

Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. 7th ed. (2005). NY, NY: John Wiley & Sons; Fungicides, Agricultural. Online Posting Date: June 15, 2000.

18. "Pesticide-use-marijuana-production" Colorado Department of Agriculture. 30 April 2015. Web. 5 May 2015. <

https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/agplants/pesticide-use-marijuana-production>.