It’s a bluebird December day in Colorado and John Todoroki is riding a high-speed chairlift to the top of Vail Mountain. At 10,000 feet, the air is so crisp, the skies so achingly blue, that it feels like the VIP section for human existence—life on Earth, only better. John savors every moment these days, but none more than these, skiing with his family and friends. He savors them like a man who could just as easily still be lying on a mud floor in a fetid Burmese prison, with no idea when or if he’ll ever get out. “When you’re in a 108-degree prison cell,” he says, gazing up the mountain into the midday sun, “you can’t imagine that you’ll ever breathe air like this again.”

I. The Raid

By any measure, John’s rookie season in the cannabis game was an epic one. In just over a year, the 62-year old American and his team created an irrigation system capable of moving 400,000 gallons of water, a soil-production unit that pulverized tons of volcano-rich, pH-optimized soil a day, and an enormous crop of hemp plants bursting with cannabidiol, better known as CBD. And they were doing it with the government’s blessing in a region of central Myanmar (formerly Burma) with an unreliable municipal power and water supply, and where the average worker has a fourth-grade education. III M Global Nutraceuticals was the first hemp business in Myanmar to receive an operating license from the state government.

It wasn’t until John’s son Alex saw drone footage of the farm in Mandalay that he fully grasped what they’d accomplished. “Once you get this bird’s-eye view,” Alex says, “you’re just like, Jesus, this is huge.”

By March 2019, III M had cultivated two strains of hemp that were extremely low in the intoxicating chemical compound THC and high in the medicinal CBD. The booming CBD industry is projected to be a multibillion-dollar global business in the next few years, and John was thinking bigger than the CBD lattes and nighttime eye creams that had come to define the American market after the 2018 farm bill legalized hemp production in the United States. Already III M’s research on growing CBD-rich industrial hemp had been promised to a large South American health care company, and its precious CBD extracts would go to a renewable energy titan. Together, the two deals were potentially worth tens of millions of dollars over the next five years. John’s lofty goal: “We’re going to be the largest wholesaler of commercial hemp in the world.”

Engineering and entrepreneurship had always come easily to John. During his sophomore year at Western State College of Colorado, he moved with a bunch of guys to an off-campus ranch house that practically required them to throw regular keg parties. Though he barely drank, John knew there had to be a smarter way to keep a keg cold than by dropping it into a bucket lined with leaky bags of ice. So he drove down to a mountaineering outfitter in Boulder and quizzed them about the thermodynamics they used in their winter gear. Then, after some trial and error, he came up with a moldable foam that kept kegs cold without flooding the kitchen with ice melt.

That foam, as it turned out, was also ideal for insulating and transporting medical matter—blood, plasma, organs for transplant—and Todo Corp was born. John sold the company less than two years later for a sum he says was in the low seven figures. He never did get his college degree.

The young John Todoroki was not a frugal millionaire. He bought a place in Beaver Creek, Colorado, a Mercedes sedan, and his first Porsche 911. He was living in L.A., going to USC football games, partying with the Anheuser-Busch distributors now using his foam to ship beer. A few years later he settled down in Colorado, where he met Ann. They were married in 1989, when John was 32, and had two sons, Alex and Jake. John mostly tended to his investments, participating in a series of mergers and acquisitions and embarking on real estate developments at home and abroad. In the early 2000s, one particularly complex project brought him to D.C. and put him in contact with, as he puts it, “the fringes of one government agency or another.” By the time the deal was closed, John had mostly stopped working for himself and began freelancing for the government, “promoting American values around the world” in places like Prague, Sarajevo, Moldova, Ukraine, Montenegro, and Hong Kong.

Work trips brought him to Myanmar in 2014 and 2015, and he fell in love with the country. He had always believed in the transformational power of agriculture—his mother grew up on a vegetable farm in Greeley, Colorado—and he began thinking about starting an agribusiness in poor, opportunity-starved Myanmar. The country had ideal agricultural conditions—a year-round growing season, soil and water that were free of the metals and contaminants common in most industrialized countries, and cheap labor—but it lacked the refrigeration and transportation needed to export many crops. “You grow what you can eat and what your grandfather grew,” John says, of the region’s subsistence economy. And it would stay that way, unless the people were trained to farm something other than chickpeas and rice.

“People, planet, profit,” John liked to say. “I know, it’s a cheap phrase that people throw around loosely, but that was the idea.”

So what could they grow that had a robust market and could be extracted into a portable, consumable extract? Vanilla? Ginger? How about high-quality, all-natural CBD? Alex had told his father about CBD and prescribed it for a toothache. “I took a few drops and it worked great,” John says. “Plus it helped me sleep.” They started researching.

For three weeks in 2017, Alex and John apprenticed at a hemp operation in Rifle, Colorado. John would stash the Lexus and they’d blend in with the day laborers. “These pot guys were high all the time,” John says, “and they’d just talk. Extracting data from them was very easy.” From these conversations and others, John calculated that the Colorado growers were spending $1.32 per plant. He estimated that his cost in Southeast Asia—which many CBD analysts believe to be the industry’s next frontier—would be six cents.

Thomas Bentley was one of those pot guys. And if John saw Thomas as just a loose-lipped stoner, Thomas saw John as a weed business arriviste—too blinded by CBD’s bright future to respect cannabis’ illicit past. Now that hemp was legal, Bentley had gotten used to seeing guys like John in the fields. “It was a whole new class of investor,” Bentley says. “Older, well-to-do, Republican.” But Thomas set aside his gripes when that affluent interloper offered something no other growers were: a Burmese adventure.

A little more than a year after John and Alex’s apprenticeship, III M was up and running in Myanmar, with a team of growers, soil scientists, aquaponics experts, and biochemists. They spent months trying out different strains, soil combinations, irrigation methods, and fertilizers— “bat shit, cow shit, goat shit, we tried them all.” John credits the shit, or his willingness to handle it, anyway, with winning over the 200 local Burmese they’d hired to work for them. “I got down in the shit with them,” he says. “That’s how I got their respect.

“People, planet, profit,” he likes to say. “I know, it’s a cheap phrase that people throw around loosely, but that was the idea: Put people first and make sure it’s good for the planet, then worry about the profit.”

III M offered what few other local employers did: vocational training, overtime, and pay equity between men and women. John had to meet with village elders three times to convince them to accept that last stipulation. John and his partners brought in a doctor from Yangon (formerly Rangoon) to provide checkups, a first for nearly all of III M’s employees, including grandmothers in their fifties. They found cases of hepatitis A, B, and C, bandaged flesh wounds, and treated one case of flesh-eating virus.

By April 2019, the farm was close to self-sufficient. John, Alex, Thomas Bentley, and another grower John had imported from Colorado were now laying the groundwork for a second farm, 500 miles east in Chiang Mai, Thailand. They started growing kenaf, a tester crop for hemp, at the Chiang Mai farm while they waited for a license to grow the real thing. If that went well, John dreamed of global expansion: “This doesn’t just work in Myanmar. It will work in India, South America, parts of Africa. Any equatorial region where there’s a poverty issue.”

For a brief, hopeful moment a few years ago, it looked like more than five decades of oppressive military rule was finally releasing its grip on Myanmar.

The third week of April was a big one for III M. They were hosting their first investors meeting, with backers from Portugal, Venezuela, and Panama all convening in Southeast Asia to tour the operation. The plan was to visit the Chiang Mai site first, then make the short flight to Myanmar and the 90-minute drive to “the RIC”—as John called the farm, for Research Innovation Center—where they would see row after row of five-foot-tall hemp plants ripening in the blazing sun.

John had two principal partners: Douglas Soe Lin, a Burmese American architect from Bethesda, Maryland, who’d had already arrived in Bangkok, and Martin Pun, III M’s Burmese-Chinese CEO, who was coming in from Honolulu to meet them in Thailand the next day. Each partner had his own role. Soe Lin knew lots of investors. Pun spoke Burmese and had the government contacts necessary to secure the permit to grow the country’s first legal hemp. And John was the guy who got things done on the ground.

On the morning of Tuesday, April 23, John was up early as usual, checking messages and getting ready for a day at the Thailand farm. One message stood out from the rest: a message from Martin Pun. There was no text, just an attachment to a Facebook video showing soldiers, with rifles slung across their chests, ransacking the greenhouse in Mandalay, trashing the fields in their military trucks, and hacking down crops with machetes.

For a brief, hopeful moment a few years ago, it looked like more than five decades of oppressive military rule was finally releasing its grip on Myanmar.

In 2015, the military junta, or Tatmadaw, effectively ceded power to a democratically elected civilian government led by opposition leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, the daughter of Aung San, a revolutionary who had led Burma’s drive for independence from the British in the late 1940s. Aung San Suu Kyi, now 74 and known as The Lady, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991 and spent 15 years under house arrest during the 1990s and 2000s before finally breaking through with a landslide victory. The rise of her National League for Democracy (NLD) was exalted as an end to the Tatmadaw, but these hopes quickly faded.

Today, most of the citizens in this majority-Buddhist country of about 56 million see the NLD and its civilian government as aligned with the same military power structure it was supposed to replace. Meanwhile, the world has come to see The Lady as something more sinister: Last year, Myanmar, represented by Aung San Suu Kyi, was summoned to the Hague to address charges of persecution and mass displacement of millions of Muslim-minority Rohingya. From Nobel laureate and Democratic reformer to allegations of genocide and mass deportation in just a few years.

These shifts at the highest levels of government had little effect on the lives of ordinary Burmese like the ones who worked for John Todoroki. To them, whether the country was called Burma or Myanmar, whether it was ruled by the Tatmadaw or a freely elected government, the British or the narcos or some combination of them all, the problem was the same: Connections and corruption determined who made money and who got jobs, who had clean water and indoor plumbing and electricity, and who didn’t.

Doing business here involved plenty of petty hassles, especially for a foreigner, and that’s what John assumed was happening that night at the farm: a misunderstanding that needed clearing up. He was more annoyed than alarmed. Fucking Burma, he thought.

As soon as they saw the video of the raid, John and Alex caught the next flight back to Mandalay, eager to straighten out the mess. When John got to the RIC, he’d show them paperwork detailing the various permissions III M had been granted to grow hemp provided it contained minuscule levels of THC—less than 0.3%. Attempting to produce legal cannabis in a Golden Triangle country, which continues to supply a sizable chunk of the region’s heroin, opium, and methamphetamine, and where the sale of narcotics (marijuana included) often carries a life sentence, requires considerable nerve. It’s something only someone confident in their ability to navigate the laws and customs of Southeast Asia would attempt. The stakeholders of III M thought they had both.

John and Alex landed in Mandalay in the early afternoon and decided they would stay at their hotel in the city that night and assess the situation before driving to the RIC in the morning. By now they were used to the commute. Alex would usually catch an extra hour of sleep in the back of the Ford pickup while his father blared Creedence and the Stones, smoking American Spirits and barreling down the jungle roads.

John spent the afternoon making phone calls—to his lawyers, his partners, his family, to the RIC itself, where the situation was getting worse by the hour. The police had taken two employees into custody: Ko Shein Latt, or “Shein,” was a contractor in his mid-thirties who had built most of the irrigation system; Ma Shun Lae Myat Noe, or “Myat,” was a chatty, sociable 22-year-old intern who’d only started working for III M three weeks earlier. She’d learned English at a college in Mandalay and had been working as the farm’s translator.

The “raid” hadn’t been menacing at first. It started more like an exploration than a seizure. Myat showed the police around, explaining the generator system, pointing out the tidy stone path John had designed. But a few hours later, she was under arrest.

As John learned all this over the phone, his confidence dissolved. This can’t be good, he thought. He wanted Alex and the other Americans out of Myanmar as soon as possible. “Get the next flight to Thailand,” he told Alex. “Just get out of here.”

As Alex climbed into a cab bound for the airport, John had a moment of doubt: “Hey Alex, do you think maybe I should go with you?”

Alex calmed his father down: “Even the lawyer said that they won’t arrest an American.”

Later that night, John was getting ready for bed when there was a knock at the door. Six or seven police and military officers barged into the hotel room and started barking at John in broken English. They ordered him to stand in a corner while they searched the room.

I have to speak to someone in authority, John thought. He had the confidence of the innocent—and the entitlement of an American. I have to just power through this. I have the paperwork, I’m in the right, and these guys are fuckin’ wrong.

While the officers conducted their search, John emailed his partner Doug for help: “Getting a visit by the police. You may have to make a call to the ambassador.”

The police marched John out of the hotel, put him in the back of an old Toyota sedan, and they drove into the night, destination unknown. It dawned on John that he might not make it through the night alive.

What are they going to do, he thought, take me to a field and shoot me?

They made a few stops at police outposts along the way. At one, he snapped a photo of the Burmese sign at the gate and sent it to Doug in case he disappeared.

Doug later emailed back: “Don’t talk. Just tell them about meeting with chief minister [who had granted their hemp permit]… Call U.S. Embassy for help too. You are an American. They won’t torture you.”

It was a long, disorienting night. In the morning, they finally arrived at the RIC, and John saw scores of agents swarming the farm, pulling up plants, dismantling everything, documenting it all for evidence. He realized this wasn’t a misunderstanding he could “clear up” with a lawyer and some official-looking paperwork. For the first time, he knew he was screwed.

“I was the only Asian kid in my school,” John says. “I got in more fights than anyone you know.”

Every branch of the Myanmar police was there—the neighborhood, the township, the district, the region of Mandalay, the drug enforcement division, and the Special Branch, one element of Myanmar’s vast intelligence apparatus—and not one of them was interested in seeing permits or hearing John explain the distinctions between CBD and THC, hemp from cannabis.

He still had his phone, which he used to warn his partners. Again, he emailed Doug in Bangkok: “Promise me you won’t come back to Myanmar.”

If the sight of his crops being yanked from the ground was dispiriting to John, the sight of Myat and Shein was devastating. They were being held in the greenhouse office. Myat was sobbing, slumped against the wall. Shein sat, weary and confused, with his head in his hands. Dozens of workers had come from their nearby villages and gathered at the RIC to watch as the authorities destroyed their year’s worth of work.

The police then loaded Myat, Shein, and John into a truck that was guarded by half a dozen police with rifles. The truck drove away, followed by three other police vehicles. They had no idea where they were going, or why.

II. Prison

When John was five, he began studying judo at a Buddhist center in Denver, realizing early on that he had a focus and discipline the other students lacked. “I got in more fights than anyone you know,” John says. “I was the only Asian kid in my school.”

It was Denver in the early ’60s, a decade after the Korean War, two since Pearl Harbor, and John was an all-purpose Asian villain for backyard war games and schoolyard taunts. (His father, a second-generation American born in Oakland, spent the first years of World War II in a Wyoming internment camp.) John kept practicing, studying, focusing... and the fights he got into outside judo got shorter and shorter. He says that when he was 11 or 12, he was a national junior champion, landing on the cover of Judo magazine.

Now, at 62, his focus and discipline would be put to the test like never before.

Eventually, the truck carrying John, Myat, and Shein reached a squat, cinder block building in the township of Ngazun, where they were turned over to a greasy-palmed police captain they came to call “the Snake.”

The Snake took a special interest in his prosperous-looking Japanese American guest. He confiscated John’s phone and demanded that he tell him the code.

John refused. “Go fuck yourself,” he told him. The Snake said if he didn’t give him the code, he’d be in prison for a long time.

“I don’t care,” John said. “I’m not giving you the code.” The stalemate continued. “Go fuck yourself,” John said again.

At this, the Snake welcomed John and Shein into their new home, a 23-by-25-foot cell packed with nearly two dozen inmates and a shared hole in the muddy floor for a toilet. Myat was transferred to the women’s area of the prison.

Days later, John asked for a phone so he could call the U.S. Embassy. The Snake refused. John kept pressing, until eventually the Snake said he could borrow his phone, but only to call his wife, not the embassy.

John called Ann in Colorado. “If I have to stay here,” he told her, “I’m not gonna make it.”

The jail didn’t provide inmates with food or water, and if you were lucky enough, as John, Shein, and Myat were, to have a friend or a family member show up with a loaf of bread, some peanut butter, or a couple of oranges, the guards had to be bribed into actually giving it to you. In fact, every point of contact with the outside world was an opportunity for graft.

The guards never let the inmates outside, even for a moment. John and Shein remained in their cell 24 hours a day, sitting on the floor in the unbearable heat, trying to ignore the moans of their cellmates and the rank stench coming from the hole in the floor. Every morning John would claim his meager share of the wall, a patch of concrete to lean against, and defend it all day long if he had to.

The prisoners slept inches apart on blankets laid over the floor. At night, the cell’s population would swell, with scorpions and other nocturnal creatures crawling in to join them. Not that anyone could sleep. The guards woke them every hour on the hour, slamming a bell 11 times for 11 p.m., 12 times for midnight, etc. They pounded whatever cheap liquor their petty bribes could buy them, and fucked with whomever they liked. John knew it could have been worse. Like most prisoners, he was sometimes beaten on the backs of his legs with bamboo sticks, but they never used their batons on him.

But the isolation was punishing enough. They were completely cut off from the outside world, and John had no one to speak to and no information on the RIC or his family.

The next test came in the form of a psychopathic inmate who set his sights on the five-foot-six American.

After 30 days in Ngazun, John, Myat, and Shein were transferred 50 miles southwest to Myingyan Prison. Here, John and Shein shared a tiny cell. The beds were wooden pallets. The toilet was, again, a hole in the floor. They were permitted to wash twice a week, from a communal trough that ensured bacteria and disease flowed freely from one inmate to another.

Built in the late 19th century, Myingyan is one of Myanmar’s oldest, most notorious prisons, having held untold numbers of murderers, addicts, and thieves, but also political prisoners, journalists, dissidents—in some cases, the very people for whom John had worked behind the scenes to keep out of places like this. In January 2015, he helped orchestrate the release of a Muslim physician, Dr. Tun Aung, who’d been unjustly jailed for his involvement in a violent protest in western Myanmar a few years earlier. Now, John would get a taste of the conditions he’d fought against.

The next test came in the form of a psychopathic inmate who set his sights on the five-foot-six American. The guy was street-hardened and sinewy, the undisputed alpha of the high-security area. He often dropped blackbirds with a slingshot in the prison yard and spit-roasted them over a fire he’d build in an old paint can for dinner. But when he stepped to John, inching his face closer and closer, John locked in on his eyes and prayed for a draw. They stood there for what seemed like hours, until the younger man gave in, bumping John with a shoulder as he turned. When John shoved him back, some mutual respect was achieved.

John didn’t have to hunt blackbirds to eat at Myingyan. Three or four times a week, his assistant made the trip to the prison and bribed a full cast of guards and administrators (six or seven of them at $7 each) to give John, Shein, and Myat the food she brought them—bread, peanut butter, occasionally a styrofoam container of local takeout: rice and a greasy piece of meat. John’s favorite meal was his assistant’s homemade chicken soup.

As Myingyan’s sole English speaker—on the men’s side anyway, since Myat was again being held on the women’s side—John had few companions among his fellow inmates. He befriended one of the weakest, a Thai addict in his sixties, frail and covered in gang tattoos, with whom he often shared the food he smuggled in from the outside. He also became close with another inmate who had been a captain in the military until he was imprisoned for marrying two women at once. The man had a contraband cellphone he let John use for a price and only once in a while. One day, John used it to call his youngest son, Jake, who was a senior at Montana State. “The tone of his voice,” Jake recalls. “He sounded broken. He was saying, ‘I don’t know how long... this could be forever.’ There was no optimism in his voice, no power to fight back. That made me feel really bad... scared. Like, what if he never came back?”

Jake sent his father anything he could find that might boost his spirits or strengthen his resolve—a Bob Dylan lyric or a quote from the Khalil Gibran book he was reading. He’d write it down, take a photo, and send it via WhatsApp to his father’s assistant. She’d then transcribe the message on paper, roll it into a tube, and slip it into the casing of a ballpoint pen she’d smuggle in to John.

“Those messages,” he would later say, “probably saved my life.”

III. Purgatory

Twice a month, John made two court appearances—one in Ngazun, where he faced drug and seed cultivation charges, and another in Myingyan, where he faced more serious narcotics and death penalty charges. (Shein and Myat were also brought to court on the same schedule.) The hearings were usually short and inconclusive, and in a language John didn’t understand. The courts never provided a translator, and John’s lawyer spoke limited English. The whole process was conducted under a cloud of uncertainty. This is not unusual in Myanmar, where a defendant might attend a year or more of bimonthly hearings and never hear a verdict. There’s too much money to be made in drawing out the process. Every hearing is an opportunity to extract another bribe—especially from foreigners.

During at least two hearings, John says, the prosecution heard witness testimony before John and his lawyers had even arrived. It didn’t matter, really, since none of the judges were interested in the crucial evidence—the permission the chief minister of Mandalay had granted III M Global Nutraceuticals to grow industrial hemp. Instead, the court repeatedly cited a 1993 law specifying that there was no legal distinction between hemp and marijuana: All cannabis, regardless of its THC content, was considered marijuana.

“John is like the grass beneath the feet of two fighting buffaloes,” explains Min Htin, a Burmese business professor who did some consulting work at the RIC. “He’s caught in a power struggle between the local Mandalay government, which is elected, and the Ministry of Home Affairs, which is appointed.” Home Affairs oversees the police, who retain the right to raid any farm they suspect of drug activity without consent of the provincial government.

The court hearings routinely attracted truckloads of III M’s workers and villagers who knew Myat and Shein, and what the farm meant to the community. They’d fill the cramped courtrooms, shouting and crying in protest.

After each hearing it was back to Myingyan Prison, to the floor John shared with Shein and whatever David Baldacci thriller he’d managed to have smuggled in. Twice a week the inmates were given gray, greasy gruel John never ate, and a daily bucket of fly-covered rice. They were allowed to walk circles in the prison yard, but the heat was oppressive, potentially deadly.

At my age, John thought, my body can’t handle this. He got weaker and weaker, and his mental state withered along with his hope. After more than a month, he could feel himself giving up, giving in, convinced that he’d never get out alive. If my life is over now, he pondered, am I proud of what I’ve done, what I’ve left behind? And his answer was, Yeah. I am.

John wasn’t entirely alone. He had a fixer on the outside—we’ll call him Joe—who was working whatever connections and greasing any palms he could. Joe was a border kid, raised between Thailand and Burma. He is cagey about his professional history. Suffice to say, he possesses a rare set of skills that John Todoroki desperately needed right now. Joe laid down a well-placed bribe or two, and that cash—along with a doctor’s note testifying to the danger of John’s heat-induced blood pressure, now 160/140—helped get him sent to the prison hospital. John looked forward to a brief respite from the putrid cell.

Yet somehow the hospital was worse: less sanitary, more menacing, than the prison itself. There was blood on the floor and splattered on the walls. John contracted the MRSA bacteria, a particularly tough infection that’s resistant to most common antibiotics and can become flesh-eating. The MRSA took hold in John’s lungs, producing a persistent, phlegmy cough and crippling lethargy. He developed sores on his neck and arms.

Salvation came in the form of twice daily injections of gentamicin, an antibiotic so harsh most physicians have either stopped prescribing it altogether or limit it to about a week. John was on it for 15 days. The antibiotic got rid of the infection, but it damaged his kidneys in the process.

But every new ailment, every assault on John’s body, was another step toward freedom. Any ailment John didn’t already have, he was willing to fake or at least embellish. So on July 25, the day of his hearing for medical bail, his assistant rented an ambulance to drive him to court.

The ambulance pulled up to the low-slung cinder block courthouse in Myingyan, and John emerged with an IV and a saline bag. An assistant steadied him as he hobbled into the building, a frail old man who had come to plead for mercy.

More than a hundred villagers had made the long journey, crowding three or more to a motorcycle and piling into pickups, to hear their boss described by prosecutors as a drug lord and an agent of American greed. Then they heard John’s lawyers detail his medical condition. When the judge began speaking, John kept his eyes on an elderly farmer to whom he’d once given an irrigation pump. The farmer never missed a court hearing, and John had come to rely on his reaction to interpret the judge’s speech. The farmer suddenly shot two thumbs up and burst into a smile, and the room erupted.

“We all cried and were hugging each other,” John’s assistant recalls. “It felt like we’d accomplished something.” John paid 300 million kyat (about $200,000) and was released on medical bail.

After the hearing, the villagers pushed their way up to the judge’s bench. One after another, they came, 10 or 15 at a time, dropping to their knees to bow and show their support. It took 20 minutes to get through them all. When the last group moved out of the courtroom, the judge stared down at his desk, and then he started to cry too.

The post-prison ritual, even if you’ve only been sprung long enough to reduce your blood pressure and get some CT scans, invariably involves food, and the first thing John did upon leaving Myingyan was set upon a plate of duck and cashews and vegetables at a local restaurant. As he washed his meal down with a rare glass of wine, he thought, There’s no happier day in a man’s life than the day he walks out of a Burmese prison.

And yet his release fell far short of true freedom. He returned to the comforts of his hotel, the Mercure Mandalay Hill Resort, but he couldn’t escape the fact that Myat and Shein were still in prison for the crime of coming to work for him, or that, barring some dramatic reversal of fortune, he’d be rejoining them at any time, whether or not his health had recovered.

Medical bail was its own twisted limbo: He couldn’t leave the hotel or travel anywhere within Mandalay province without being followed by two or three police officers. Family visits were essentially prohibited, but at least he could talk and text. Now that he was out, he resumed paying more than 200 III M employees a portion of the wages they would have made if they were able to work. And he finally had the support of the U.S. Embassy. (He was told that the Americans had withheld official assistance until DEA agents were able to inspect the RIC and field-test the plants to confirm that they weren’t helping an American drug dealer.) John’s contact at the embassy arranged for him to travel to Yangon to get kidney and lung scans at one of the country’s only MRI facilities.

“I opened that can of worms,” he thought, “and now everyone knows I’m willing to pay — the police, the prosecutors, everyone.”

Mentally, though, being out was harder than prison in some ways. Inside, the constant struggle for survival made him focused and stubbornly upbeat. Now he felt hopeless, marooned in his hotel room. He wasn’t behind bars, but he was shackled by survivor’s guilt and despair. He dragged a chair from the room and left it out on the eighth-floor balcony, so he could step up and over at a moment’s notice: He would jump before he would go back to prison.

His mind drifted toward violence against others, too. Almost every night, the same dream: He has a samurai sword and he’s swinging, whacking the heads off of Burmese soldiers, one after the other, killing them all.

The only antidote to his hopelessness was action. A Burmese journalist set up a meeting with Mandalay’s chief minister, U Zaw Myint Maung, the very man who’d issued the permits that supposedly granted III M the right to grow cannabis for CBD. U Zaw Myint Maung had been in prison for several years himself, as a political prisoner, and John hoped he would take up his case inside the government. John and his assistant went to the minister’s home for breakfast. He lived in a spacious, three-story house in the British colonial style, with police guards at the gate and a large foyer. On either side of the foyer, John noticed rooms stacked with AC units, cases of liquor, electronics, and unwrapped gifts.

Over bowls of mohinga, a tangy rice noodle soup that is Burma’s most popular breakfast dish, the chief minister assessed John’s predicament and blithely waved away the permits he himself had issued. The 1993 narcotics law that John had allegedly violated made no distinction between marijuana and hemp, THC and CBD, and so, the minister told him, he would be going back to Myingyan. “You’ll be fine in prison,” the minister told him. (John’s assistant knew better than to translate that on the spot.) Chief Minister U Zaw Myint Maung did not return messages asking for comment.

John could have begun plotting an escape then, crossing the porous Laotian border or slipping into Thailand, but Shein and Myat remained in jail, and John was their only hope. He visited Myat’s parents and Shein’s wife and toddler son, updating them on his legal efforts and trying to provide what little comfort he could. They never blamed him, but John’s relative freedom, the fact that he was living in an air-conditioned hotel and not Myingyan Prison with the others, compounded his guilt.

At least there was good news about his health: It was still deteriorating.

Summer turned to fall, and he pressed on. He made his case to the U.S. State Department, American media contacts, Japan’s ambassador to Myanmar, anyone who could help. He agitated and advocated on Shein and Myat’s behalf as well as his own, and this being Myanmar, that meant money. Through Joe, the fixer, John attempted to pay their way to justice, paying off this local strongman or that government official, an attorney here, a military general there. By October, he’d exhausted his options and his funds. He estimates he spent more than $500,000 and accomplished exactly nothing beyond sapping the money he was using to keep paying his former employees.

He’d been played. I opened that can of worms, he thought, and now everyone knows I’m willing to pay—the police, the prosecutors, everyone. Now I have no choice but to pay and pay and it becomes a business for them.

At least there was good news about his health: It was still deteriorating. One of John’s doctors determined that he’d probably had a stroke in prison and a grand mal seizure. This would buy him a little more time, but more importantly, give him a valid excuse to go back to Yangon for more scans. There, he could move about without surveillance.

IV. The Bridge

Joe had been visiting friends in Virginia, way back in late April, when he first heard of John Todoroki. He got a call from a friend who had a friend who somehow knew John, and the friend briefed Joe on John’s arrest. Joe had been thinking about how he might get John out of Myanmar since that first phone call last spring, and now, six months later, he was about to get his chance.

He had a plan, an assistant, and a king cab pickup truck that was a dead ringer for the official vehicles used by the military. Its bed was wrapped in green canvas and there was a government sticker on the windshield. The rear seats of the cab had been replaced with the same big black box that Myanmar’s soldiers have in the cabs of their trucks.

On a dank, rainy October afternoon, John dressed in black and climbed into the box. In Joe’s pocket were 30 crisp $100 bills, a last-ditch incentive for a soldier to unsee the fugitive crouching in the box. There were five police checkpoints between Yangon and the border crossing, and John was dreading every one. John’s picture had been in the newspaper and on the equivalent of the evening news. Discovery by even the lowliest soldier in the most forgotten jungle outpost would almost certainly send him straight back to Myingyan. An alleged narco caught trying to flee justice, he would have no more cards left to play.

They drove out of Yangon at 4 p.m., so most of their checkpoint interactions would coincide with the prime drinking hours of the soldiers manning them. Joe was counting on other distractions as well. “They don’t do much work at night,” Joe says. “They don’t care. They have girlfriends from the nearby villages who can’t visit during the day.”

Every checkpoint was sheer terror for John, crammed into the black box, but they were blessedly anticlimactic: Three of the five were unmanned and they passed through the others without incident.

After 13 hours, they arrived at the Thai border. It was 5 a.m. and the crossing was closed. They killed time in a tea shop, where Joe made John wear sunglasses and a baseball cap and keep his back to the door. The American pot farmer. Even here, hundreds of miles from the RIC, he might be recognized.

The U.S. Embassy had issued John a new passport (in his own name), and Joe had paid a Myanmar immigration officer $300 for a stamp. A long line started to form of mostly poor, mostly desperate Burmese, looking to improve their fortunes in Thailand or beyond. Finally, John was ready to make his move. Joe told John to walk across the concrete bridge, assuring him that he and his associate would be right behind him. “If you get through,” Joe told him, “we’ll catch up in 10 or 15 minutes.”

“And if I don’t?” John asked.

“You won’t see us at all,” Joe said.

Then John strolled casually across the quarter-mile bridge to Thailand. At the checkpoint, when he presented his new passport to the Thai border agent, he struggled to keep his composure. Again, though, luck was on his side. The agent was too busy arguing with someone on his phone to scrutinize the stamp or even pay much attention to the passport before waving him through.

He made his way through the checkpoint, and on to freedom. He waited until he’d walked around the corner, behind a building and out of sight. Then he started jumping up and down, thinking, I am a free motherfucker! I am free!

Joe and his assistant caught up and were waiting on the other side as promised, in a different truck, which then whisked them away. An hour later, they stopped for chicken, but John was too hopped up on adrenaline and sleep deprivation to eat much. It wasn’t until they got to Bangkok, after taking a quick flight from Mae Sot, Thailand, that John’s appetite returned. Across the street from his Bangkok hotel, John spotted his beloved golden arches. “I made a beeline for it,” he says now, smiling at the memory. “Big Mac, large fries, and a Coca-Cola. It was the best McDonald’s I ever had.”

What John was able to build in Myanmar was exceptional in many ways. A win-win-win, as John saw it. People. Planet. Profit. And it was—for a while. But Burma is Burma, a country where Nobel laureates lead a country alleged to have turned a blind eye to genocide, and where jails are filled with innocent people who bet on the wrong horse. Attempting to pull off what John and his partners very nearly pulled off may have been overly optimistic, a step too far in the direction of progress. Because when people, planet, and profit met guns and drug laws and money, the winning stopped and the losing started. The villagers lost. They had hoped the American CBD farm would lift their community and train their children for something more than growing chickpeas and rice. John lost, too—money, labor, six months of his life. (And in late February, the court in Myingyan issued a warrant for his arrest.) But no one lost more than Shein and Myat.

“I’m eating $25 burgers at 10,000 feet and they’re in prison. I know what they’re going through.”

When John and I meet in Colorado in December, he is months removed from a minor stroke, his kidney function is compromised, and he may need to have the damaged part of his left lung removed, but you wouldn’t know it by the way he skis. He makes smooth, precise turns, with an economy and grace borne of 50-plus years of mountain muscle memory. He’s an aggressive “see you at the bottom” kind of skier. Watching him on the chairlift, breathing deeply of his freedom, is a stirring sight: an American who has experienced enough of the despots and corrupt governments of the world to appreciate the United States in a way few Americans can or do.

“I just feel so fucking guilty,” he says when the subject turns to Myat and Shein. His voice cracks. “I’m eating $25 burgers at 10,000 feet and they’re in prison. I know what they’re going through.”

Since he got home in November, John stepped up his campaign to help get Myat and Shein out of prison—writing letters to members of Congress he’s aided in the past, attaching Myat and Shein’s cause to persecution charges against Myanmar, trying to shame the U.S. Department of Commerce into supporting the imprisoned employees of an American company. But nothing was working. And there was little reason for hope.

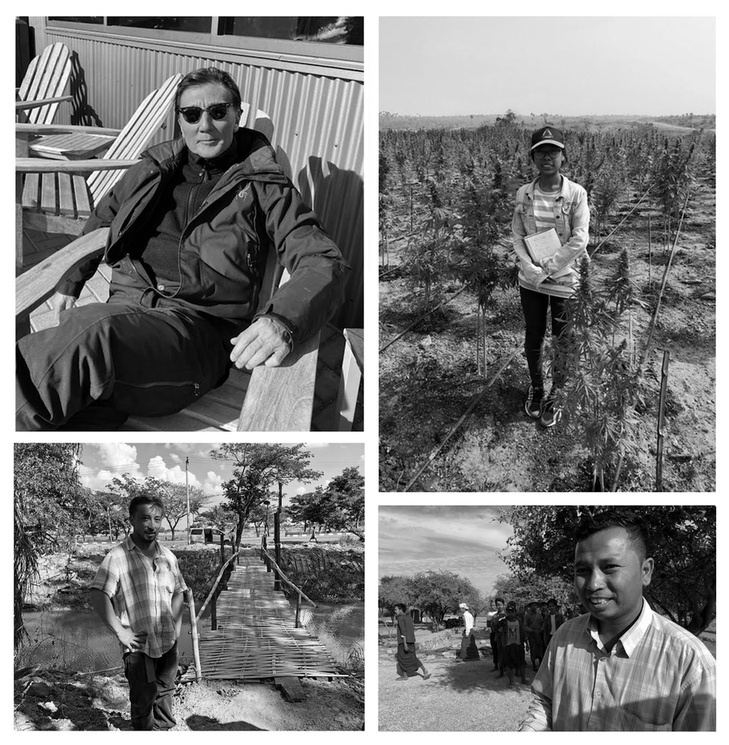

Clockwise from top left: John Todoroki, Ma Shun Lae Myat Noe, Ko Shein Latt, and Alex Todoroki. Photos courtesy of John Todoroki.

And then, in early February, there was a hearing and a hasty announcement. After subjecting Myat to ten months in prison, the court dropped the charges against her, concluding that there “was no evidence” that she “was responsible for the plantation” where she’d interned for a total of 21 days. When she was escorted out of Myingyan Prison, she immediately collapsed into her mother’s arms.

Shein was less fortunate. He remains in prison and still faces up to 15 years for allegedly “cultivating cannabis and possession of restricted chemicals.”

John has had an abundance of time to sit and think about the work he did in Burma, and he has no regrets. “Maybe all these things didn’t work out perfectly, but they would have worked. They were working. And we got fucked.”

His normally kind, placid face shows a slight twist toward anger. “It wasn’t so much being naive, as it was being fucked. There’s a difference. And that’s where the anger lies.”

Every day in prison, John would read two things: a letter from his son Jake urging him to stay strong, and a poem that was shared with him by the one prison warden who had shown him any kindness. John made a handwritten copy of the poem—“Invictus” by William Ernest Henley—on a piece of paper that he kept on the floor beneath the blanket he slept on. The poem is a Victorian ode to perseverance, and John says the stoicism and stubborn will it conjures got him through each day. Beneath the four short stanzas, he added something of a reminder to himself. “What we created,” he wrote, “made a small part of the world better. Not many can make this claim. Be proud.”

I. The Raid

By any measure, John’s rookie season in the cannabis game was an epic one. In just over a year, the 62-year old American and his team created an irrigation system capable of moving 400,000 gallons of water, a soil-production unit that pulverized tons of volcano-rich, pH-optimized soil a day, and an enormous crop of hemp plants bursting with cannabidiol, better known as CBD. And they were doing it with the government’s blessing in a region of central Myanmar (formerly Burma) with an unreliable municipal power and water supply, and where the average worker has a fourth-grade education. III M Global Nutraceuticals was the first hemp business in Myanmar to receive an operating license from the state government.

It wasn’t until John’s son Alex saw drone footage of the farm in Mandalay that he fully grasped what they’d accomplished. “Once you get this bird’s-eye view,” Alex says, “you’re just like, Jesus, this is huge.”

By March 2019, III M had cultivated two strains of hemp that were extremely low in the intoxicating chemical compound THC and high in the medicinal CBD. The booming CBD industry is projected to be a multibillion-dollar global business in the next few years, and John was thinking bigger than the CBD lattes and nighttime eye creams that had come to define the American market after the 2018 farm bill legalized hemp production in the United States. Already III M’s research on growing CBD-rich industrial hemp had been promised to a large South American health care company, and its precious CBD extracts would go to a renewable energy titan. Together, the two deals were potentially worth tens of millions of dollars over the next five years. John’s lofty goal: “We’re going to be the largest wholesaler of commercial hemp in the world.”

Engineering and entrepreneurship had always come easily to John. During his sophomore year at Western State College of Colorado, he moved with a bunch of guys to an off-campus ranch house that practically required them to throw regular keg parties. Though he barely drank, John knew there had to be a smarter way to keep a keg cold than by dropping it into a bucket lined with leaky bags of ice. So he drove down to a mountaineering outfitter in Boulder and quizzed them about the thermodynamics they used in their winter gear. Then, after some trial and error, he came up with a moldable foam that kept kegs cold without flooding the kitchen with ice melt.

That foam, as it turned out, was also ideal for insulating and transporting medical matter—blood, plasma, organs for transplant—and Todo Corp was born. John sold the company less than two years later for a sum he says was in the low seven figures. He never did get his college degree.

The young John Todoroki was not a frugal millionaire. He bought a place in Beaver Creek, Colorado, a Mercedes sedan, and his first Porsche 911. He was living in L.A., going to USC football games, partying with the Anheuser-Busch distributors now using his foam to ship beer. A few years later he settled down in Colorado, where he met Ann. They were married in 1989, when John was 32, and had two sons, Alex and Jake. John mostly tended to his investments, participating in a series of mergers and acquisitions and embarking on real estate developments at home and abroad. In the early 2000s, one particularly complex project brought him to D.C. and put him in contact with, as he puts it, “the fringes of one government agency or another.” By the time the deal was closed, John had mostly stopped working for himself and began freelancing for the government, “promoting American values around the world” in places like Prague, Sarajevo, Moldova, Ukraine, Montenegro, and Hong Kong.

Work trips brought him to Myanmar in 2014 and 2015, and he fell in love with the country. He had always believed in the transformational power of agriculture—his mother grew up on a vegetable farm in Greeley, Colorado—and he began thinking about starting an agribusiness in poor, opportunity-starved Myanmar. The country had ideal agricultural conditions—a year-round growing season, soil and water that were free of the metals and contaminants common in most industrialized countries, and cheap labor—but it lacked the refrigeration and transportation needed to export many crops. “You grow what you can eat and what your grandfather grew,” John says, of the region’s subsistence economy. And it would stay that way, unless the people were trained to farm something other than chickpeas and rice.

“People, planet, profit,” John liked to say. “I know, it’s a cheap phrase that people throw around loosely, but that was the idea.”

So what could they grow that had a robust market and could be extracted into a portable, consumable extract? Vanilla? Ginger? How about high-quality, all-natural CBD? Alex had told his father about CBD and prescribed it for a toothache. “I took a few drops and it worked great,” John says. “Plus it helped me sleep.” They started researching.

For three weeks in 2017, Alex and John apprenticed at a hemp operation in Rifle, Colorado. John would stash the Lexus and they’d blend in with the day laborers. “These pot guys were high all the time,” John says, “and they’d just talk. Extracting data from them was very easy.” From these conversations and others, John calculated that the Colorado growers were spending $1.32 per plant. He estimated that his cost in Southeast Asia—which many CBD analysts believe to be the industry’s next frontier—would be six cents.

Thomas Bentley was one of those pot guys. And if John saw Thomas as just a loose-lipped stoner, Thomas saw John as a weed business arriviste—too blinded by CBD’s bright future to respect cannabis’ illicit past. Now that hemp was legal, Bentley had gotten used to seeing guys like John in the fields. “It was a whole new class of investor,” Bentley says. “Older, well-to-do, Republican.” But Thomas set aside his gripes when that affluent interloper offered something no other growers were: a Burmese adventure.

A little more than a year after John and Alex’s apprenticeship, III M was up and running in Myanmar, with a team of growers, soil scientists, aquaponics experts, and biochemists. They spent months trying out different strains, soil combinations, irrigation methods, and fertilizers— “bat shit, cow shit, goat shit, we tried them all.” John credits the shit, or his willingness to handle it, anyway, with winning over the 200 local Burmese they’d hired to work for them. “I got down in the shit with them,” he says. “That’s how I got their respect.

“People, planet, profit,” he likes to say. “I know, it’s a cheap phrase that people throw around loosely, but that was the idea: Put people first and make sure it’s good for the planet, then worry about the profit.”

III M offered what few other local employers did: vocational training, overtime, and pay equity between men and women. John had to meet with village elders three times to convince them to accept that last stipulation. John and his partners brought in a doctor from Yangon (formerly Rangoon) to provide checkups, a first for nearly all of III M’s employees, including grandmothers in their fifties. They found cases of hepatitis A, B, and C, bandaged flesh wounds, and treated one case of flesh-eating virus.

By April 2019, the farm was close to self-sufficient. John, Alex, Thomas Bentley, and another grower John had imported from Colorado were now laying the groundwork for a second farm, 500 miles east in Chiang Mai, Thailand. They started growing kenaf, a tester crop for hemp, at the Chiang Mai farm while they waited for a license to grow the real thing. If that went well, John dreamed of global expansion: “This doesn’t just work in Myanmar. It will work in India, South America, parts of Africa. Any equatorial region where there’s a poverty issue.”

For a brief, hopeful moment a few years ago, it looked like more than five decades of oppressive military rule was finally releasing its grip on Myanmar.

The third week of April was a big one for III M. They were hosting their first investors meeting, with backers from Portugal, Venezuela, and Panama all convening in Southeast Asia to tour the operation. The plan was to visit the Chiang Mai site first, then make the short flight to Myanmar and the 90-minute drive to “the RIC”—as John called the farm, for Research Innovation Center—where they would see row after row of five-foot-tall hemp plants ripening in the blazing sun.

John had two principal partners: Douglas Soe Lin, a Burmese American architect from Bethesda, Maryland, who’d had already arrived in Bangkok, and Martin Pun, III M’s Burmese-Chinese CEO, who was coming in from Honolulu to meet them in Thailand the next day. Each partner had his own role. Soe Lin knew lots of investors. Pun spoke Burmese and had the government contacts necessary to secure the permit to grow the country’s first legal hemp. And John was the guy who got things done on the ground.

On the morning of Tuesday, April 23, John was up early as usual, checking messages and getting ready for a day at the Thailand farm. One message stood out from the rest: a message from Martin Pun. There was no text, just an attachment to a Facebook video showing soldiers, with rifles slung across their chests, ransacking the greenhouse in Mandalay, trashing the fields in their military trucks, and hacking down crops with machetes.

For a brief, hopeful moment a few years ago, it looked like more than five decades of oppressive military rule was finally releasing its grip on Myanmar.

In 2015, the military junta, or Tatmadaw, effectively ceded power to a democratically elected civilian government led by opposition leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, the daughter of Aung San, a revolutionary who had led Burma’s drive for independence from the British in the late 1940s. Aung San Suu Kyi, now 74 and known as The Lady, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991 and spent 15 years under house arrest during the 1990s and 2000s before finally breaking through with a landslide victory. The rise of her National League for Democracy (NLD) was exalted as an end to the Tatmadaw, but these hopes quickly faded.

Today, most of the citizens in this majority-Buddhist country of about 56 million see the NLD and its civilian government as aligned with the same military power structure it was supposed to replace. Meanwhile, the world has come to see The Lady as something more sinister: Last year, Myanmar, represented by Aung San Suu Kyi, was summoned to the Hague to address charges of persecution and mass displacement of millions of Muslim-minority Rohingya. From Nobel laureate and Democratic reformer to allegations of genocide and mass deportation in just a few years.

These shifts at the highest levels of government had little effect on the lives of ordinary Burmese like the ones who worked for John Todoroki. To them, whether the country was called Burma or Myanmar, whether it was ruled by the Tatmadaw or a freely elected government, the British or the narcos or some combination of them all, the problem was the same: Connections and corruption determined who made money and who got jobs, who had clean water and indoor plumbing and electricity, and who didn’t.

Doing business here involved plenty of petty hassles, especially for a foreigner, and that’s what John assumed was happening that night at the farm: a misunderstanding that needed clearing up. He was more annoyed than alarmed. Fucking Burma, he thought.

As soon as they saw the video of the raid, John and Alex caught the next flight back to Mandalay, eager to straighten out the mess. When John got to the RIC, he’d show them paperwork detailing the various permissions III M had been granted to grow hemp provided it contained minuscule levels of THC—less than 0.3%. Attempting to produce legal cannabis in a Golden Triangle country, which continues to supply a sizable chunk of the region’s heroin, opium, and methamphetamine, and where the sale of narcotics (marijuana included) often carries a life sentence, requires considerable nerve. It’s something only someone confident in their ability to navigate the laws and customs of Southeast Asia would attempt. The stakeholders of III M thought they had both.

John and Alex landed in Mandalay in the early afternoon and decided they would stay at their hotel in the city that night and assess the situation before driving to the RIC in the morning. By now they were used to the commute. Alex would usually catch an extra hour of sleep in the back of the Ford pickup while his father blared Creedence and the Stones, smoking American Spirits and barreling down the jungle roads.

John spent the afternoon making phone calls—to his lawyers, his partners, his family, to the RIC itself, where the situation was getting worse by the hour. The police had taken two employees into custody: Ko Shein Latt, or “Shein,” was a contractor in his mid-thirties who had built most of the irrigation system; Ma Shun Lae Myat Noe, or “Myat,” was a chatty, sociable 22-year-old intern who’d only started working for III M three weeks earlier. She’d learned English at a college in Mandalay and had been working as the farm’s translator.

The “raid” hadn’t been menacing at first. It started more like an exploration than a seizure. Myat showed the police around, explaining the generator system, pointing out the tidy stone path John had designed. But a few hours later, she was under arrest.

As John learned all this over the phone, his confidence dissolved. This can’t be good, he thought. He wanted Alex and the other Americans out of Myanmar as soon as possible. “Get the next flight to Thailand,” he told Alex. “Just get out of here.”

As Alex climbed into a cab bound for the airport, John had a moment of doubt: “Hey Alex, do you think maybe I should go with you?”

Alex calmed his father down: “Even the lawyer said that they won’t arrest an American.”

Later that night, John was getting ready for bed when there was a knock at the door. Six or seven police and military officers barged into the hotel room and started barking at John in broken English. They ordered him to stand in a corner while they searched the room.

I have to speak to someone in authority, John thought. He had the confidence of the innocent—and the entitlement of an American. I have to just power through this. I have the paperwork, I’m in the right, and these guys are fuckin’ wrong.

While the officers conducted their search, John emailed his partner Doug for help: “Getting a visit by the police. You may have to make a call to the ambassador.”

The police marched John out of the hotel, put him in the back of an old Toyota sedan, and they drove into the night, destination unknown. It dawned on John that he might not make it through the night alive.

What are they going to do, he thought, take me to a field and shoot me?

They made a few stops at police outposts along the way. At one, he snapped a photo of the Burmese sign at the gate and sent it to Doug in case he disappeared.

Doug later emailed back: “Don’t talk. Just tell them about meeting with chief minister [who had granted their hemp permit]… Call U.S. Embassy for help too. You are an American. They won’t torture you.”

It was a long, disorienting night. In the morning, they finally arrived at the RIC, and John saw scores of agents swarming the farm, pulling up plants, dismantling everything, documenting it all for evidence. He realized this wasn’t a misunderstanding he could “clear up” with a lawyer and some official-looking paperwork. For the first time, he knew he was screwed.

“I was the only Asian kid in my school,” John says. “I got in more fights than anyone you know.”

Every branch of the Myanmar police was there—the neighborhood, the township, the district, the region of Mandalay, the drug enforcement division, and the Special Branch, one element of Myanmar’s vast intelligence apparatus—and not one of them was interested in seeing permits or hearing John explain the distinctions between CBD and THC, hemp from cannabis.

He still had his phone, which he used to warn his partners. Again, he emailed Doug in Bangkok: “Promise me you won’t come back to Myanmar.”

If the sight of his crops being yanked from the ground was dispiriting to John, the sight of Myat and Shein was devastating. They were being held in the greenhouse office. Myat was sobbing, slumped against the wall. Shein sat, weary and confused, with his head in his hands. Dozens of workers had come from their nearby villages and gathered at the RIC to watch as the authorities destroyed their year’s worth of work.

The police then loaded Myat, Shein, and John into a truck that was guarded by half a dozen police with rifles. The truck drove away, followed by three other police vehicles. They had no idea where they were going, or why.

II. Prison

When John was five, he began studying judo at a Buddhist center in Denver, realizing early on that he had a focus and discipline the other students lacked. “I got in more fights than anyone you know,” John says. “I was the only Asian kid in my school.”

It was Denver in the early ’60s, a decade after the Korean War, two since Pearl Harbor, and John was an all-purpose Asian villain for backyard war games and schoolyard taunts. (His father, a second-generation American born in Oakland, spent the first years of World War II in a Wyoming internment camp.) John kept practicing, studying, focusing... and the fights he got into outside judo got shorter and shorter. He says that when he was 11 or 12, he was a national junior champion, landing on the cover of Judo magazine.

Now, at 62, his focus and discipline would be put to the test like never before.

Eventually, the truck carrying John, Myat, and Shein reached a squat, cinder block building in the township of Ngazun, where they were turned over to a greasy-palmed police captain they came to call “the Snake.”

The Snake took a special interest in his prosperous-looking Japanese American guest. He confiscated John’s phone and demanded that he tell him the code.

John refused. “Go fuck yourself,” he told him. The Snake said if he didn’t give him the code, he’d be in prison for a long time.

“I don’t care,” John said. “I’m not giving you the code.” The stalemate continued. “Go fuck yourself,” John said again.

At this, the Snake welcomed John and Shein into their new home, a 23-by-25-foot cell packed with nearly two dozen inmates and a shared hole in the muddy floor for a toilet. Myat was transferred to the women’s area of the prison.

Days later, John asked for a phone so he could call the U.S. Embassy. The Snake refused. John kept pressing, until eventually the Snake said he could borrow his phone, but only to call his wife, not the embassy.

John called Ann in Colorado. “If I have to stay here,” he told her, “I’m not gonna make it.”

The jail didn’t provide inmates with food or water, and if you were lucky enough, as John, Shein, and Myat were, to have a friend or a family member show up with a loaf of bread, some peanut butter, or a couple of oranges, the guards had to be bribed into actually giving it to you. In fact, every point of contact with the outside world was an opportunity for graft.

The guards never let the inmates outside, even for a moment. John and Shein remained in their cell 24 hours a day, sitting on the floor in the unbearable heat, trying to ignore the moans of their cellmates and the rank stench coming from the hole in the floor. Every morning John would claim his meager share of the wall, a patch of concrete to lean against, and defend it all day long if he had to.

The prisoners slept inches apart on blankets laid over the floor. At night, the cell’s population would swell, with scorpions and other nocturnal creatures crawling in to join them. Not that anyone could sleep. The guards woke them every hour on the hour, slamming a bell 11 times for 11 p.m., 12 times for midnight, etc. They pounded whatever cheap liquor their petty bribes could buy them, and fucked with whomever they liked. John knew it could have been worse. Like most prisoners, he was sometimes beaten on the backs of his legs with bamboo sticks, but they never used their batons on him.

But the isolation was punishing enough. They were completely cut off from the outside world, and John had no one to speak to and no information on the RIC or his family.

The next test came in the form of a psychopathic inmate who set his sights on the five-foot-six American.

After 30 days in Ngazun, John, Myat, and Shein were transferred 50 miles southwest to Myingyan Prison. Here, John and Shein shared a tiny cell. The beds were wooden pallets. The toilet was, again, a hole in the floor. They were permitted to wash twice a week, from a communal trough that ensured bacteria and disease flowed freely from one inmate to another.

Built in the late 19th century, Myingyan is one of Myanmar’s oldest, most notorious prisons, having held untold numbers of murderers, addicts, and thieves, but also political prisoners, journalists, dissidents—in some cases, the very people for whom John had worked behind the scenes to keep out of places like this. In January 2015, he helped orchestrate the release of a Muslim physician, Dr. Tun Aung, who’d been unjustly jailed for his involvement in a violent protest in western Myanmar a few years earlier. Now, John would get a taste of the conditions he’d fought against.

The next test came in the form of a psychopathic inmate who set his sights on the five-foot-six American. The guy was street-hardened and sinewy, the undisputed alpha of the high-security area. He often dropped blackbirds with a slingshot in the prison yard and spit-roasted them over a fire he’d build in an old paint can for dinner. But when he stepped to John, inching his face closer and closer, John locked in on his eyes and prayed for a draw. They stood there for what seemed like hours, until the younger man gave in, bumping John with a shoulder as he turned. When John shoved him back, some mutual respect was achieved.

John didn’t have to hunt blackbirds to eat at Myingyan. Three or four times a week, his assistant made the trip to the prison and bribed a full cast of guards and administrators (six or seven of them at $7 each) to give John, Shein, and Myat the food she brought them—bread, peanut butter, occasionally a styrofoam container of local takeout: rice and a greasy piece of meat. John’s favorite meal was his assistant’s homemade chicken soup.

As Myingyan’s sole English speaker—on the men’s side anyway, since Myat was again being held on the women’s side—John had few companions among his fellow inmates. He befriended one of the weakest, a Thai addict in his sixties, frail and covered in gang tattoos, with whom he often shared the food he smuggled in from the outside. He also became close with another inmate who had been a captain in the military until he was imprisoned for marrying two women at once. The man had a contraband cellphone he let John use for a price and only once in a while. One day, John used it to call his youngest son, Jake, who was a senior at Montana State. “The tone of his voice,” Jake recalls. “He sounded broken. He was saying, ‘I don’t know how long... this could be forever.’ There was no optimism in his voice, no power to fight back. That made me feel really bad... scared. Like, what if he never came back?”

Jake sent his father anything he could find that might boost his spirits or strengthen his resolve—a Bob Dylan lyric or a quote from the Khalil Gibran book he was reading. He’d write it down, take a photo, and send it via WhatsApp to his father’s assistant. She’d then transcribe the message on paper, roll it into a tube, and slip it into the casing of a ballpoint pen she’d smuggle in to John.

“Those messages,” he would later say, “probably saved my life.”

III. Purgatory

Twice a month, John made two court appearances—one in Ngazun, where he faced drug and seed cultivation charges, and another in Myingyan, where he faced more serious narcotics and death penalty charges. (Shein and Myat were also brought to court on the same schedule.) The hearings were usually short and inconclusive, and in a language John didn’t understand. The courts never provided a translator, and John’s lawyer spoke limited English. The whole process was conducted under a cloud of uncertainty. This is not unusual in Myanmar, where a defendant might attend a year or more of bimonthly hearings and never hear a verdict. There’s too much money to be made in drawing out the process. Every hearing is an opportunity to extract another bribe—especially from foreigners.

During at least two hearings, John says, the prosecution heard witness testimony before John and his lawyers had even arrived. It didn’t matter, really, since none of the judges were interested in the crucial evidence—the permission the chief minister of Mandalay had granted III M Global Nutraceuticals to grow industrial hemp. Instead, the court repeatedly cited a 1993 law specifying that there was no legal distinction between hemp and marijuana: All cannabis, regardless of its THC content, was considered marijuana.

“John is like the grass beneath the feet of two fighting buffaloes,” explains Min Htin, a Burmese business professor who did some consulting work at the RIC. “He’s caught in a power struggle between the local Mandalay government, which is elected, and the Ministry of Home Affairs, which is appointed.” Home Affairs oversees the police, who retain the right to raid any farm they suspect of drug activity without consent of the provincial government.

The court hearings routinely attracted truckloads of III M’s workers and villagers who knew Myat and Shein, and what the farm meant to the community. They’d fill the cramped courtrooms, shouting and crying in protest.

After each hearing it was back to Myingyan Prison, to the floor John shared with Shein and whatever David Baldacci thriller he’d managed to have smuggled in. Twice a week the inmates were given gray, greasy gruel John never ate, and a daily bucket of fly-covered rice. They were allowed to walk circles in the prison yard, but the heat was oppressive, potentially deadly.

At my age, John thought, my body can’t handle this. He got weaker and weaker, and his mental state withered along with his hope. After more than a month, he could feel himself giving up, giving in, convinced that he’d never get out alive. If my life is over now, he pondered, am I proud of what I’ve done, what I’ve left behind? And his answer was, Yeah. I am.

John wasn’t entirely alone. He had a fixer on the outside—we’ll call him Joe—who was working whatever connections and greasing any palms he could. Joe was a border kid, raised between Thailand and Burma. He is cagey about his professional history. Suffice to say, he possesses a rare set of skills that John Todoroki desperately needed right now. Joe laid down a well-placed bribe or two, and that cash—along with a doctor’s note testifying to the danger of John’s heat-induced blood pressure, now 160/140—helped get him sent to the prison hospital. John looked forward to a brief respite from the putrid cell.

Yet somehow the hospital was worse: less sanitary, more menacing, than the prison itself. There was blood on the floor and splattered on the walls. John contracted the MRSA bacteria, a particularly tough infection that’s resistant to most common antibiotics and can become flesh-eating. The MRSA took hold in John’s lungs, producing a persistent, phlegmy cough and crippling lethargy. He developed sores on his neck and arms.

Salvation came in the form of twice daily injections of gentamicin, an antibiotic so harsh most physicians have either stopped prescribing it altogether or limit it to about a week. John was on it for 15 days. The antibiotic got rid of the infection, but it damaged his kidneys in the process.

But every new ailment, every assault on John’s body, was another step toward freedom. Any ailment John didn’t already have, he was willing to fake or at least embellish. So on July 25, the day of his hearing for medical bail, his assistant rented an ambulance to drive him to court.

The ambulance pulled up to the low-slung cinder block courthouse in Myingyan, and John emerged with an IV and a saline bag. An assistant steadied him as he hobbled into the building, a frail old man who had come to plead for mercy.

More than a hundred villagers had made the long journey, crowding three or more to a motorcycle and piling into pickups, to hear their boss described by prosecutors as a drug lord and an agent of American greed. Then they heard John’s lawyers detail his medical condition. When the judge began speaking, John kept his eyes on an elderly farmer to whom he’d once given an irrigation pump. The farmer never missed a court hearing, and John had come to rely on his reaction to interpret the judge’s speech. The farmer suddenly shot two thumbs up and burst into a smile, and the room erupted.

“We all cried and were hugging each other,” John’s assistant recalls. “It felt like we’d accomplished something.” John paid 300 million kyat (about $200,000) and was released on medical bail.

After the hearing, the villagers pushed their way up to the judge’s bench. One after another, they came, 10 or 15 at a time, dropping to their knees to bow and show their support. It took 20 minutes to get through them all. When the last group moved out of the courtroom, the judge stared down at his desk, and then he started to cry too.

The post-prison ritual, even if you’ve only been sprung long enough to reduce your blood pressure and get some CT scans, invariably involves food, and the first thing John did upon leaving Myingyan was set upon a plate of duck and cashews and vegetables at a local restaurant. As he washed his meal down with a rare glass of wine, he thought, There’s no happier day in a man’s life than the day he walks out of a Burmese prison.

And yet his release fell far short of true freedom. He returned to the comforts of his hotel, the Mercure Mandalay Hill Resort, but he couldn’t escape the fact that Myat and Shein were still in prison for the crime of coming to work for him, or that, barring some dramatic reversal of fortune, he’d be rejoining them at any time, whether or not his health had recovered.

Medical bail was its own twisted limbo: He couldn’t leave the hotel or travel anywhere within Mandalay province without being followed by two or three police officers. Family visits were essentially prohibited, but at least he could talk and text. Now that he was out, he resumed paying more than 200 III M employees a portion of the wages they would have made if they were able to work. And he finally had the support of the U.S. Embassy. (He was told that the Americans had withheld official assistance until DEA agents were able to inspect the RIC and field-test the plants to confirm that they weren’t helping an American drug dealer.) John’s contact at the embassy arranged for him to travel to Yangon to get kidney and lung scans at one of the country’s only MRI facilities.

“I opened that can of worms,” he thought, “and now everyone knows I’m willing to pay — the police, the prosecutors, everyone.”

Mentally, though, being out was harder than prison in some ways. Inside, the constant struggle for survival made him focused and stubbornly upbeat. Now he felt hopeless, marooned in his hotel room. He wasn’t behind bars, but he was shackled by survivor’s guilt and despair. He dragged a chair from the room and left it out on the eighth-floor balcony, so he could step up and over at a moment’s notice: He would jump before he would go back to prison.

His mind drifted toward violence against others, too. Almost every night, the same dream: He has a samurai sword and he’s swinging, whacking the heads off of Burmese soldiers, one after the other, killing them all.

The only antidote to his hopelessness was action. A Burmese journalist set up a meeting with Mandalay’s chief minister, U Zaw Myint Maung, the very man who’d issued the permits that supposedly granted III M the right to grow cannabis for CBD. U Zaw Myint Maung had been in prison for several years himself, as a political prisoner, and John hoped he would take up his case inside the government. John and his assistant went to the minister’s home for breakfast. He lived in a spacious, three-story house in the British colonial style, with police guards at the gate and a large foyer. On either side of the foyer, John noticed rooms stacked with AC units, cases of liquor, electronics, and unwrapped gifts.

Over bowls of mohinga, a tangy rice noodle soup that is Burma’s most popular breakfast dish, the chief minister assessed John’s predicament and blithely waved away the permits he himself had issued. The 1993 narcotics law that John had allegedly violated made no distinction between marijuana and hemp, THC and CBD, and so, the minister told him, he would be going back to Myingyan. “You’ll be fine in prison,” the minister told him. (John’s assistant knew better than to translate that on the spot.) Chief Minister U Zaw Myint Maung did not return messages asking for comment.

John could have begun plotting an escape then, crossing the porous Laotian border or slipping into Thailand, but Shein and Myat remained in jail, and John was their only hope. He visited Myat’s parents and Shein’s wife and toddler son, updating them on his legal efforts and trying to provide what little comfort he could. They never blamed him, but John’s relative freedom, the fact that he was living in an air-conditioned hotel and not Myingyan Prison with the others, compounded his guilt.

At least there was good news about his health: It was still deteriorating.

Summer turned to fall, and he pressed on. He made his case to the U.S. State Department, American media contacts, Japan’s ambassador to Myanmar, anyone who could help. He agitated and advocated on Shein and Myat’s behalf as well as his own, and this being Myanmar, that meant money. Through Joe, the fixer, John attempted to pay their way to justice, paying off this local strongman or that government official, an attorney here, a military general there. By October, he’d exhausted his options and his funds. He estimates he spent more than $500,000 and accomplished exactly nothing beyond sapping the money he was using to keep paying his former employees.

He’d been played. I opened that can of worms, he thought, and now everyone knows I’m willing to pay—the police, the prosecutors, everyone. Now I have no choice but to pay and pay and it becomes a business for them.

At least there was good news about his health: It was still deteriorating. One of John’s doctors determined that he’d probably had a stroke in prison and a grand mal seizure. This would buy him a little more time, but more importantly, give him a valid excuse to go back to Yangon for more scans. There, he could move about without surveillance.

IV. The Bridge